I have come to realize more and more how very fortunate I have been in my life. I could list many instances of this good fortune, which I surely did nothing to deserve. Just one for today: I have never had the misfortune of being entangled in the criminal justice system. It is only now that I am beginning to understand more about this monster that we - as citizens - create in an attempt to uphold the rule of law.

An excellent recent report from the New Economics Foundation is entitled Punishing Costs: How locking up children is making Britain less safe. As of February 2010, there were 2,195 10–17-year-olds imprisoned in England and Wales. 82 per cent of 12–14-year-olds sent to prison have never committed a violent offense. These seems like shocking facts, even before we know that this is a higher rate of child imprisonment than almost any other developed country. It seems all the more shocking when we learn that child imprisonment is neither a good strategy for reducing crime in the long run, nor a cost-effective strategy.

Child imprisonment is not without rationale, of course. There are indeed benefits to incarceration of children; it dramatically reduces or eliminates their ability to commit crimes and abuse drugs for the period of their imprisonment. The problem - from a cold detached perspective - is that this approach is neither effective or efficient. A year's imprisonment costs society more than £140,000. £100,000 of this is in the direct cost of imprisonment. A minimum of £40,000 of additional costs results from all the many negative consequences of imprisonment: reduced ability to earn, disconnection from education, increased criminality upon release, and reduced connection to family and community.

There are clearly better ways to deal with young offenders, including helping them (through mental health and drug services and providing paid work) before they offend.

Why then have we as a society opted to use approaches that are both less humane and less effective than alternatives when dealing with child offenders?

According to the NEF report, a key factor is a mechanical and systematic one: the central government bears the entire cost of prison placements while local councils are responsible for the services that might keep kids out of prison. In other words, imprisonment can seem to councils like a respite from the duties and cots of dealing with children in trouble. Imprisonment is more attractive locally because it reduces problems and costs. It's only a disaster when we see the bigger picture.

As a person who believes in the possibility for goodness in everyone, I have a profound moral objection to a criminal justice system that does not aim to reform offenders whenever possible and give them the possibility of living with dignity. I have a profound moral objection to a system that it more inclined to spend money to punish and sequester offenders than to help them avoid becoming offenders in the first place. I would have these objections even if the system were cost effective. To find that it is neither humane nor effective should outrage all of us. This is no way to treat human beings - especially children.

Wednesday, 16 June 2010

Monday, 14 June 2010

Being wrong as a spiritual practice

Failure! Oh, that is a bad word. "You failed" seems like one of the most deflating things we can hear. When I was a laboratory scientist, failure was part of the game. Everything was an experiment. Sometimes things were successful and sometimes they failed. That's just how it works.

In other parts of our lives, trying and failing just seems much worse than not trying at all.

Over at Ministrare, my colleague Sean Dennison wrote recently about human fallibility and forgiveness. He describes something that all of us probably see in organizations (and feel in ourselves) too often - the fear of making mistakes:

I’m not convinced, though, that a strong theology of sin makes anyone less susceptible to this sort of thing. I haven't seen a lot of conservative Christians coming up to me lately to say "sorry - I was wrong." Quite the contrary. So if orthodox Christian belief is a key to being more willing to be wrong, there must not be many true orthodox Christians - ones who really, really believe the teachings of their faith (and that is certainly very possible.)

I'm not even sure that this fear of mistakes is so much a particularly Unitarian (or non-Christian) thing as it is a 21st century, mean old work-a-day world thing. It is part of the materialistic tool kit required for “success” in the regular world. People have bosses and want to get ahead. You get ahead by being right - even if you're wrong. People don’t just drop that ethos when they walk into church (unfortunately).

A minister - or anyone in a position of influence - has some opportunity to change that at least a bit. The most effective approach is modeling. If I admit when I'm wrong - often and loudly - and show that the world does not come to a sudden end, it may make members of my congregation more willing to do the same. And, if we can accept that failure is not a disaster, we become more willing to try new things. So what if it doesn't work? We'll never know unless we try. (One more experienced colleague advised me to make deliberate mistakes and then admit them!)

Sean's post got me thinking about something else though. I'm very focused on spiritual practice at the moment and especially thinking about non-traditional practices.

We know that needing to be right is destructive of relationships and communities. We know it makes us timid and defensive. What if - as a spiritual practice - we make a point of finding something we are (or were) wrong about and admitting it. First, admit it ourselves, but under the condition that we are going to be accepting and gentle about it. "I put too much salt in the hummus." And my response: "So what! The Queen's not coming for dinner tonight!"

And then maybe admit it to a person you trust. Start small: "you know, it turns out I was wrong about dolphins just being gay sharks.* Oops!" See what happens... If it's not a disaster, then maybe we can learn that we don't actually have to be right all the time.

One of the central notions of spiritual growth is putting aside the stuff that distracts us from authenticity, connection, and wholeness. It's not about creating something new, but about cultivating and revealing what is already present - although fragile or obscured. If we learn that have to be right all the time, maybe that helps us to put aside the overriding ego thing just a bit

For this week, I think I'll give this a try and find something every day to be wrong about! Anyone else willing to give it a go?

To begin for today, I was wrong to buy that Tesco 'value' paper shredder. Although it was cheap, it keeps jamming all the time. I should have spent more to get something more reliable.

Oh, I was wrong ignoring the half and half brown and green composting rule too. the compost is getting stinky.

And while I'm at it, the readings I chose for the service today were no better than just OK...

Now, let's see if the sky falls!

*Glee reference

In other parts of our lives, trying and failing just seems much worse than not trying at all.

Over at Ministrare, my colleague Sean Dennison wrote recently about human fallibility and forgiveness. He describes something that all of us probably see in organizations (and feel in ourselves) too often - the fear of making mistakes:

I’ve watched people, committees, and whole congregations become paralyzed by this anxiety. I’ve seen ideas that were destroyed by an almost compulsive need to imagine every possible thing that could go wrong and try to figure out how to avoid them all.His take on it is that Unitarians are more afraid to make mistakes than others and that this comes down to theology. He chalks this up to the Unitarian move away from certain aspects of Christianity:

when we moved away from orthodox Christian theologies of sin and redemption, we gave up the stories, theology, and practices of forgiveness as well.I could not agree more that the fear of making mistakes is paralyzing. It is destructive of trust and prevents the formation of truly authentic relationships within congregations. It prevents us from growing and learning because growth always means stretching and trying something new.

I’m not convinced, though, that a strong theology of sin makes anyone less susceptible to this sort of thing. I haven't seen a lot of conservative Christians coming up to me lately to say "sorry - I was wrong." Quite the contrary. So if orthodox Christian belief is a key to being more willing to be wrong, there must not be many true orthodox Christians - ones who really, really believe the teachings of their faith (and that is certainly very possible.)

I'm not even sure that this fear of mistakes is so much a particularly Unitarian (or non-Christian) thing as it is a 21st century, mean old work-a-day world thing. It is part of the materialistic tool kit required for “success” in the regular world. People have bosses and want to get ahead. You get ahead by being right - even if you're wrong. People don’t just drop that ethos when they walk into church (unfortunately).

A minister - or anyone in a position of influence - has some opportunity to change that at least a bit. The most effective approach is modeling. If I admit when I'm wrong - often and loudly - and show that the world does not come to a sudden end, it may make members of my congregation more willing to do the same. And, if we can accept that failure is not a disaster, we become more willing to try new things. So what if it doesn't work? We'll never know unless we try. (One more experienced colleague advised me to make deliberate mistakes and then admit them!)

Sean's post got me thinking about something else though. I'm very focused on spiritual practice at the moment and especially thinking about non-traditional practices.

We know that needing to be right is destructive of relationships and communities. We know it makes us timid and defensive. What if - as a spiritual practice - we make a point of finding something we are (or were) wrong about and admitting it. First, admit it ourselves, but under the condition that we are going to be accepting and gentle about it. "I put too much salt in the hummus." And my response: "So what! The Queen's not coming for dinner tonight!"

And then maybe admit it to a person you trust. Start small: "you know, it turns out I was wrong about dolphins just being gay sharks.* Oops!" See what happens... If it's not a disaster, then maybe we can learn that we don't actually have to be right all the time.

One of the central notions of spiritual growth is putting aside the stuff that distracts us from authenticity, connection, and wholeness. It's not about creating something new, but about cultivating and revealing what is already present - although fragile or obscured. If we learn that have to be right all the time, maybe that helps us to put aside the overriding ego thing just a bit

For this week, I think I'll give this a try and find something every day to be wrong about! Anyone else willing to give it a go?

To begin for today, I was wrong to buy that Tesco 'value' paper shredder. Although it was cheap, it keeps jamming all the time. I should have spent more to get something more reliable.

Oh, I was wrong ignoring the half and half brown and green composting rule too. the compost is getting stinky.

And while I'm at it, the readings I chose for the service today were no better than just OK...

Now, let's see if the sky falls!

*Glee reference

Friday, 4 June 2010

Eeny, Meeny, Miny, Mo spirituality

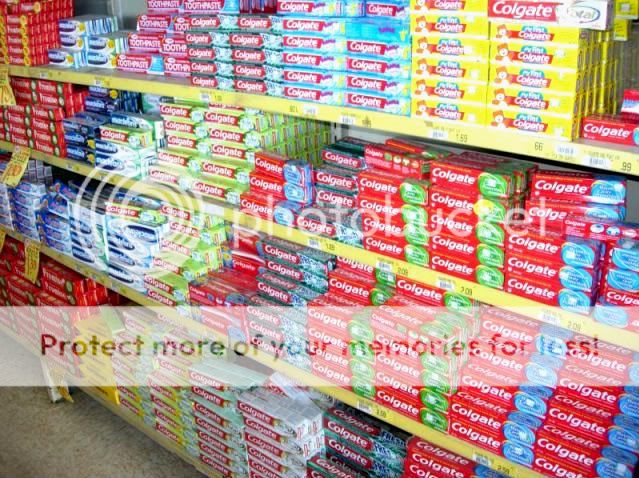

I have developed a problem shopping in large stores. It's simply that I am overwhelmed by an excess of choice. I remember being in the toothpaste section in a one of the big American supermarkets. I just wanted toothpaste - simple ordinary toothpaste - for tooth brushing. You know? Nothing special please! There had to be a good 25 feet of toothpastes. Toothpaste for tartar, toothpaste for fresh breath, toothpaste to whiten and brighten. Toothpaste with fluoride, toothpaste with mouthwash, and toothpaste with special unnamed magical ingredients that would surely win you the partner of your dreams. If that choice of contents weren't enough, you have to choose between tubes, gels, pastes, pumps, drops... and everything comes in five or six different sizes. Oh no! How can I make the 'right' choice? So many options! Help!

As I recall, I had to be rescued from the toothpaste aisle and led gently but firmly to a small mom-and-pop store that only sold two kinds of toothpaste. Done!

Now, when I shop in any large store, I remember to bring one of the most important childhood decision making tools with me: the ancient wisdom of eeny, meeny, miny, mo... It never fails.

In some ways, spiritual practice is like shopping for toothpaste. If you are a strict _____ [fill in the blank with the religion of your choice], your path is constrained and proscribed. Simple. Just like the mom-and-pop store. You can choose between two kinds of prayer. Easy enough...

If, however, you are seeking spiritual growth outside of a traditional religious structure [Unitarians included here], you are in the mega-market toothpaste aisle! You have too many choices and, like me, you may go into the overstimulation daze and choose nothing. You don't meditate because it might be better to pray, or to do yoga, or to take a walk in the park, or or or or or...

Just like the toothpaste though, there really is no right answer. Eeny meeny miny mo is not a bad way to approach the problem. The truth is that any reasonable spiritual practice will help.

Why? Because spiritual growth depends always on being present, noticing, being mindful, being connected. However you describe it, this quality of awareness is the foundation upon which everything else in the spiritual life is built. You can't notice the sacredness of life if you are not aware. You can't detect the divinity in each person if you never look in that special, deliberate way that requires slowing and focusing. You can't detect the 'still small voice' if you can't stop long enough and listen intently enough to hear.

My advice: Just pick one and start.

Yes, different practices will help in somewhat different ways. After eeny, meeny, miny, mo takes you a certain distance, you may become aware that what you need now is something that is more physical, more focused, more people-oriented, more humbling, more emotional, more intellectual, or more creative. That wisdom will emerge once you are on the path. The key is to get started.

Often incorrectly credited to Goethe, but no less important if another author is responsible, are these words:

As I recall, I had to be rescued from the toothpaste aisle and led gently but firmly to a small mom-and-pop store that only sold two kinds of toothpaste. Done!

Now, when I shop in any large store, I remember to bring one of the most important childhood decision making tools with me: the ancient wisdom of eeny, meeny, miny, mo... It never fails.

In some ways, spiritual practice is like shopping for toothpaste. If you are a strict _____ [fill in the blank with the religion of your choice], your path is constrained and proscribed. Simple. Just like the mom-and-pop store. You can choose between two kinds of prayer. Easy enough...

If, however, you are seeking spiritual growth outside of a traditional religious structure [Unitarians included here], you are in the mega-market toothpaste aisle! You have too many choices and, like me, you may go into the overstimulation daze and choose nothing. You don't meditate because it might be better to pray, or to do yoga, or to take a walk in the park, or or or or or...

Just like the toothpaste though, there really is no right answer. Eeny meeny miny mo is not a bad way to approach the problem. The truth is that any reasonable spiritual practice will help.

Why? Because spiritual growth depends always on being present, noticing, being mindful, being connected. However you describe it, this quality of awareness is the foundation upon which everything else in the spiritual life is built. You can't notice the sacredness of life if you are not aware. You can't detect the divinity in each person if you never look in that special, deliberate way that requires slowing and focusing. You can't detect the 'still small voice' if you can't stop long enough and listen intently enough to hear.

My advice: Just pick one and start.

Yes, different practices will help in somewhat different ways. After eeny, meeny, miny, mo takes you a certain distance, you may become aware that what you need now is something that is more physical, more focused, more people-oriented, more humbling, more emotional, more intellectual, or more creative. That wisdom will emerge once you are on the path. The key is to get started.

Often incorrectly credited to Goethe, but no less important if another author is responsible, are these words:

Whatever you can do, or dream you can do, begin it.Nothing could be more true of your spiritual journey. Get started, even if your choice depends on the wisdom of eeny, meeny, miny, mo.

Boldness has genius, power, and magic in it!

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)